Transcranial magnetic stimulation: A technology of the future celebrates 40 years

This year we commemorate forty years since the birth of transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), a groundbreaking technology that launched an entire field of non-invasive brain stimulation. Today, this method painlessly and without surgery helps treat depression and allows us to study the brain. Yet its origins lie in a modest British laboratory, from where it spread within a few years across the world, including numerous clinical and research centers in the Czech Republic.

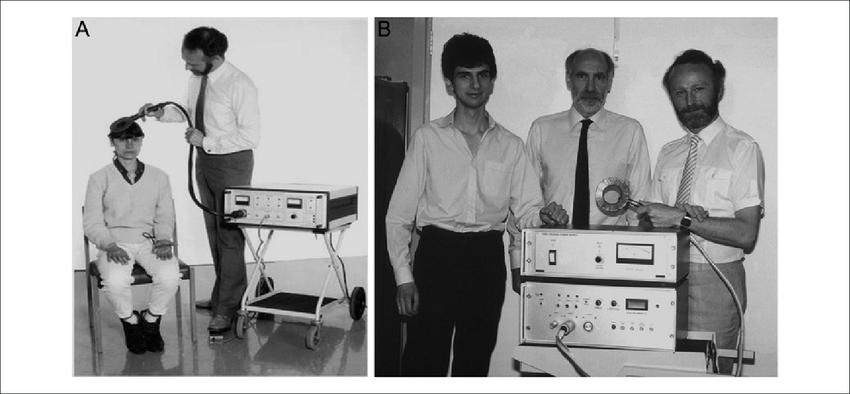

The development of TMS was led by engineer Anthony Barker from the University of Sheffield. He built the first prototype of a magnetic stimulator during his PhD studies, originally intended only for the stimulation of peripheral nerves. Although the device did not perform well for that purpose, Barker did not abandon magnetic stimulation and continued working on it purely out of scientific curiosity.

A key moment came in 1984 at a conference in London, where Barker learned about the work of Patrick Merton, who stimulated the brain using electric current. Barker immediately realized that his magnetic stimulator could be used in the same way, but painlessly, more comfortably, and more safely.

Still, he proceeded cautiously. He did not want to perform the first experiment on himself, so he wrote Merton a letter proposing a joint test. In February 1985, Barker took a train from Sheffield to London. None of the passengers knew that the two large, heavy suitcases he carried contained a device that would change the future of psychiatry and neuroscience.

In his laboratory on Queen Square, Patrick Merton was already waiting, and he became the first test subject. Magnetic stimulation of the motor cortex reliably produced hand movement, painlessly and with immediate effect. The excitement was enormous. Merton immediately phoned colleagues across London and soon lines began forming outside his lab, everyone wanted to try the "miracle" device on themselves.

Barker initially hesitated to publish the first results, but after a month he sent a short paper to The Lancet, describing the principle and potential of magnetic brain stimulation. The article was published on 11 May 1985, and the scientific response was immediate. Hundreds of letters started arriving in Sheffield from around the world. During the first year, Barker's laboratory produced six new stimulators, and he believed that would be enough. He could not have been more wrong.

Demand grew so quickly that it became clear a completely new era had begun. Barker then decided not to patent his device. He left it freely available to the scientific community so it could be further improved and widely shared. This decision fundamentally accelerated the development of the entire field of non-invasive brain stimulation and enabled the rapid adoption of TMS in both research and clinical practice.

How does TMS actually work?

This non-invasive method uses the principle of electromagnetic induction. A coil placed over the head emits rapid magnetic pulses that induce an electric current in neural tissue. This can directly trigger an action potential and activate neurons. Clinically, TMS is most commonly used to treat depression. Therapy consists of repeated sessions over several weeks, though in recent years accelerated protocols have emerged that allow effective treatment within just a few days.

Magnetic stimulation, however, has broad potential. Beyond depression, it is also used in obsessive-compulsive disorder, various forms of addiction, and is being experimentally investigated for Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease.

With the growing importance of brain stimulation in both research and clinical practice, a new professional initiative was launched this year in the Czech Republic to connect specialists from research centers across the country. The newly formed Brain Stimulation Section, operating under the Czech Society for Clinical Neurophysiology, is already bringing together experts from psychiatry, neurology, bioengineering, and other fields.

In 1985, the year the cult sci-fi Back to the Future premiered, transcranial magnetic stimulation was born from simple engineering curiosity. Today, it helps us understand the brain and treat its disorders. The establishment of the Brain Stimulation Section marks another step toward ensuring that Czech science and medicine, too, move boldly into the future.

This is a translation of an article in Czech by Mgr. Luboš Brabenec, Ph.D.

Image source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/240309313_Magnetic_Fields_in_Noninvasive_Brain_Stimulation</p>